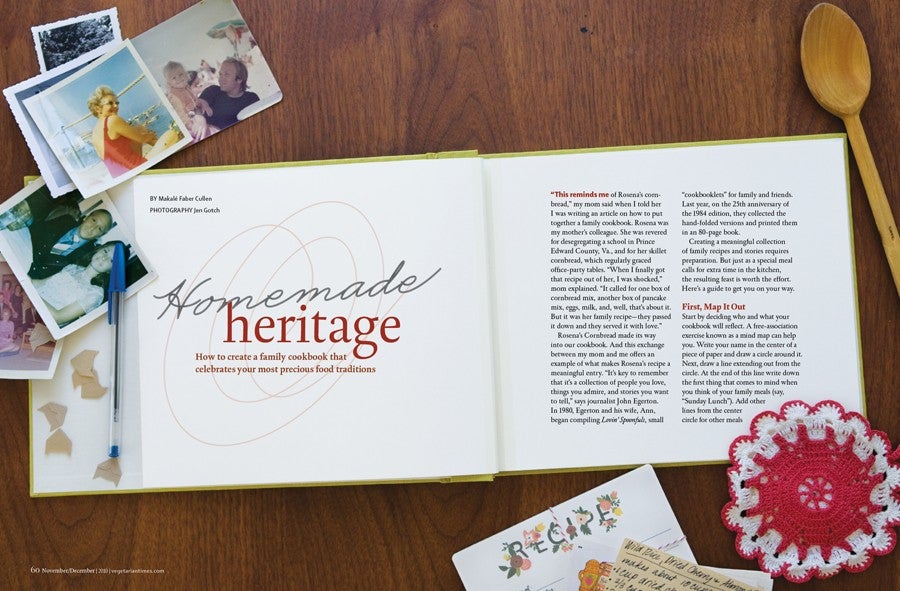

Homemade Heritage

“This reminds me of Rosena’s cornbread,” my mom said when I told her I was writing an article on how to put together a family cookbook. Rosena was my mother’s colleague. She was revered for desegregating a school in Prince Edward County, Va., and for her skillet cornbread, which regularly graced office-party tables. “When I finally got that recipe out of her, I was shocked,” mom explained. “It called for one box of cornbread mix, another box of pancake mix, eggs, milk, and, well, that’s about it. But it was her family recipe—they passed it down and they served it with love.”

Rosena’s Cornbread made its way into our cookbook. And this exchange between my mom and me offers an example of what makes Rosena’s recipe a meaningful entry. “It’s key to remember that it’s a collection of people you love, things you admire, and stories you want to tell,” says journalist John Egerton. In 1980, Egerton and his wife, Ann, began compiling Lovin’ Spoonfuls, small “cookbooklets” for family and friends. Last year, on the 25th anniversary of the 1984 edition, they collected the hand-folded versions and printed them in an 80-page book.

Creating a meaningful collection of family recipes and stories requires preparation. But just as a special meal calls for extra time in the kitchen, the resulting feast is worth the effort. Here’s a guide to get you on your way.

First, Map It Out

Start by deciding who and what your cookbook will reflect. A free-association exercise known as a mind map can help you. Write your name in the center of a piece of paper and draw a circle around it. Next, draw a line extending out from the circle. At the end of this line write down the first thing that comes to mind when you think of your family meals (say, “Sunday Lunch”). Add other lines from the center circle for other meals (“Thanksgiving,” “Birthday Party,” etc.). These ideas can be used as categories to organize your cookbook rather than the generic “Appetizers,” “Salads,” or “Entrées.” Extend lines from these first tiers to add associations to them. “Sunday Lunch” could include dishes served, tablecloths used, people invited, and music heard. This second tier offers details to sprinkle throughout the book and bring it to life.

If free-form thinking doesn’t work for you, another starting point could be a conversation with whoever does the most (and best) cooking in the family. Arrange a recipe collection meeting or a call with them. Ask for recipes that reflect the background of your family in some way. Is there a recipe the cook remembers learning from his or her parents, or a neighbor? At the end, ask for a recommendation of another family member to interview. And so on. Before long, you’ll have a list of worthy contributors.

Go on Location

Get into the kitchen—yours and your family’s. Using a camera and a notepad, document what you see. Are there tools that reflect your heritage, such as your mother’s mixing bowl or your grandmother’s cast-iron skillet? Does a pierogi press make an appearance for special-occasion meals? Take pictures of items to accompany a recipe or cook’s profile. What about pantry goods? Is there a certain kind of oil—say, sesame or palm—that offers a clue about family heritage? What about large quantities of staples, such as 20-pound bags of rice or cornmeal? Snap photos of these too. Open the fridge for more clues. Around the holidays, shelves are usually stocked with the ingredients that distinguish your family’s culinary traditions.

Get It on the Record

Once you’ve identified the voices and flavors you’ll feature, start collecting recipes. Create a template that includes the name of the cook and the dish, with space for ingredients, instructions, presentation tips, and anecdotes. Make a list of questions, such as the following:

Where did you learn this recipe?

Where do the ingredients come from (e.g., specialty shop, garden)?

Did you ever have to substitute ingredients? Has the recipe changed?

What foods or drinks do you serve with this dish?

Do you cook this dish for everyday meals or for special occasions?

When you think of this food, what comes to mind? (Aromas in your grandmother’s kitchen, getting called in for supper after playing?)

The questions can be asked over the phone, via e-mail, as a note on a Facebook page, or even recorded or videotaped in person. If cooks need to get back to you, give them a two- to four-week deadline. This provides enough time to muse and recollect, but not so much time that they’ll forget about your project. If you’re soliciting a lot of recipes, be sure to let folks know that while every submission is savored, not every one will make it into your book.

Shape It Like a Story

Imagine reading the recipe for Rosena’s Cornbread—a couple of baking mixes—without all the personal details my mother provided. You wouldn’t think much of it, would you? But knowing who Rosena was, how the cornbread was shared, and how my mom reacted when she found out the actual recipe gives it life and provides insight into all the cooks involved. “You want your cookbook to end up with the spirit of the community, its characters and quirks, its real sense of identity,” says Egerton. “A family cookbook must go beyond the plate.”

If you have a hard time thinking what to say and how to say it, ask yourself: what would you want your children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews to know about the food and the people around the table during your childhood or right now? Give depth to your cookbook characters, and readers will return to them to comfort the belly and the heart and to share traditions with future generations.

Book or Blog?

From a pamphlet printed at a copy shop to a professionally bound cookbook to a blog that may include videos, technology has made sharing recipes a creative and accessible endeavor. Each medium has a different set of considerations.

Classic Cookbook

Size A good starter size is 10 12- x 9-inch sheets printed front and back and folded in half (for 20 9- x 6-inch pages). This allows 16 pages for recipes, 2 pages for front and back covers, plus 2 pages for an introduction, a family tree, notes, or a contacts page.

Layout Most word-processing software includes tools that make it easy to transfer words and images to various page formats. You can scan and insert photos, and add your own designs and motifs to pages.

Paper and Binding Coil-binding is a classic for family cookbooks. For a handmade look, Sarah Nicholls, program manager at the Center for Book Arts, in New York, suggests “folded paper, three holes, and a simple stitch—perfect for a thin book.” There are also self-publishing websites that let you design a book online and order professionally bound copies.

Online Blog

Design Most blog-hosting websites walk you through design and layout. For continuity, create a template that can be reused as more elements are added. Decide where photos will appear, if videos can be uploaded, and how comments and stories can be shared.

Accessibility Is your family cookbook blog a site for all to see or will access be limited to loved ones? (Limiting access gives a sense of specialness while protecting privacy.) Blogs can have multiple contributors, or you can curate the recipe collection via submissions.

Updates and Exchanges A cookbook blog provides a forum for an ongoing exchange, but it requires updating to stay relevant. Schedule updates on or around birthdays and special occasions so family members continue sharing old and new traditions. A blog may require some extra work to include older family members who aren’t computer-savvy.