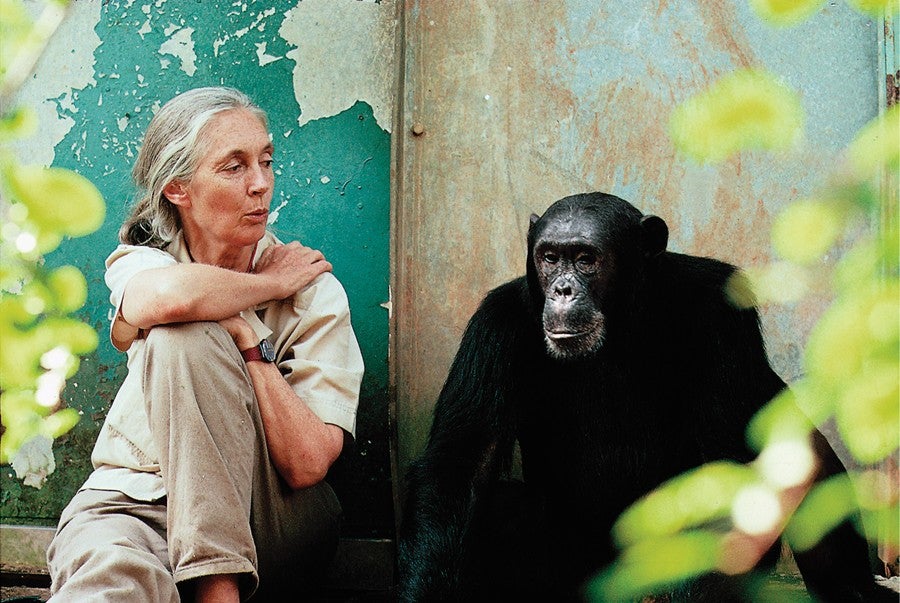

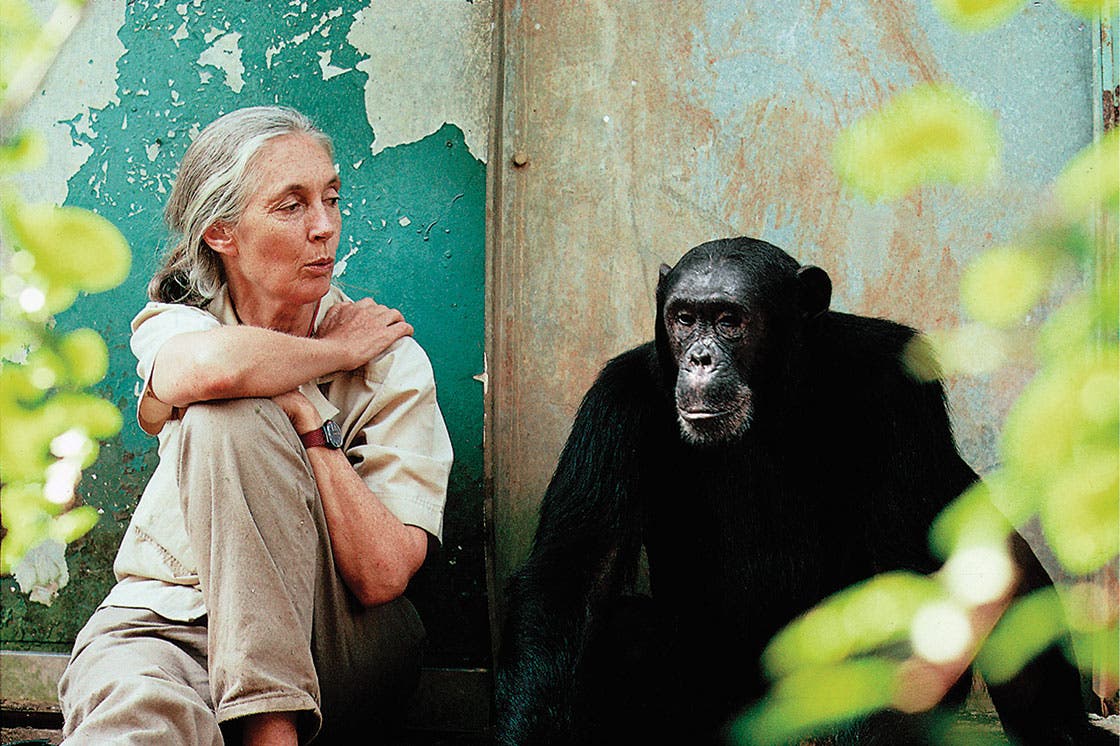

One-on-One with Jane Goodall

Nearly 50 years after she first joined legendary anthropologist Louis Leakey to study chimps in Africa, Jane Goodall, PhD, remains a force of nature herself. As leader of the international Jane Goodall Institute (janegoodall.org)which she founded in 1977 to protect primates and their habitatsshe travels the world teaching about the interconnectedness of all life and how we can help overcome ecological crises. Her 17th book, Hope for Animals and Their World, offers a renewed optimism about animals, humans, and our future together. VT caught up with Goodall, 75, a longtime vegetarian, at her family home in Bournemouth, England.

Q: In the book’s foreword, coauthor Thane Maynard writes, “I really have no idea why Jane and I are so disproportionately buoyant in such a time of loss.” Where does your hope come from?

A: Because of my endless traveling and the people I meet, I get told the good stories as well as the bad. One person I met, Don Merton in New Zealand, saved a bird called the black robin from extinction when (in 1976) only seven birds were leftthere are about 600 or something now. I’ve seen with my own eyes that if you give nature a chance, she can bloom, even though we’ve destroyed a whole ecosystem, basically.

Q: You write about “symbols of hope” you’ve collecteda leaf, a feather, tree bark. What symbols can we find in our own backyards?

A: A symbol of hope could be a little plant coming up through concrete. You can treasure a child who’s survived cancer. There are all kinds of symbols.

Q: What changes can we make in our own lives to perpetuate the arc of hope you write about?

A: The most important thing is changing the meat diet. And eat organic as much as possible. Buy locally grown foods. Boosting small farmers and family farms is incredibly important.

Q: During your travels, you must have sampled some exotic vegetarian dishes. Can you recall your favorite?

A: There is one I loved best. I was literally in the middle of nowhere, in a forest in the northern Republic of Congo, visiting people studying chimps. We were out one evening in the forest with pygmy trackers. They picked these orange mushrooms, along with a large leaf from a low-lying plantI have no idea of its name. They cooked them together; the leaves made a kind of broth. It was absolutely delicious, and the vibrant orange and green colors were so beautiful. And it was definitely vegetarian.

Q: In your new book, you write about a connection to nature you felt growing up. You still live in your childhood home. Is that connection still there?

A: Yes, absolutely. There are the same trees I climbed as a child. I see the same birdsor the descendants thereof. There are fewer insects, which is worrying. And some bird species are gone, which is also worrying. But that doesn’t mean they can’t come back.