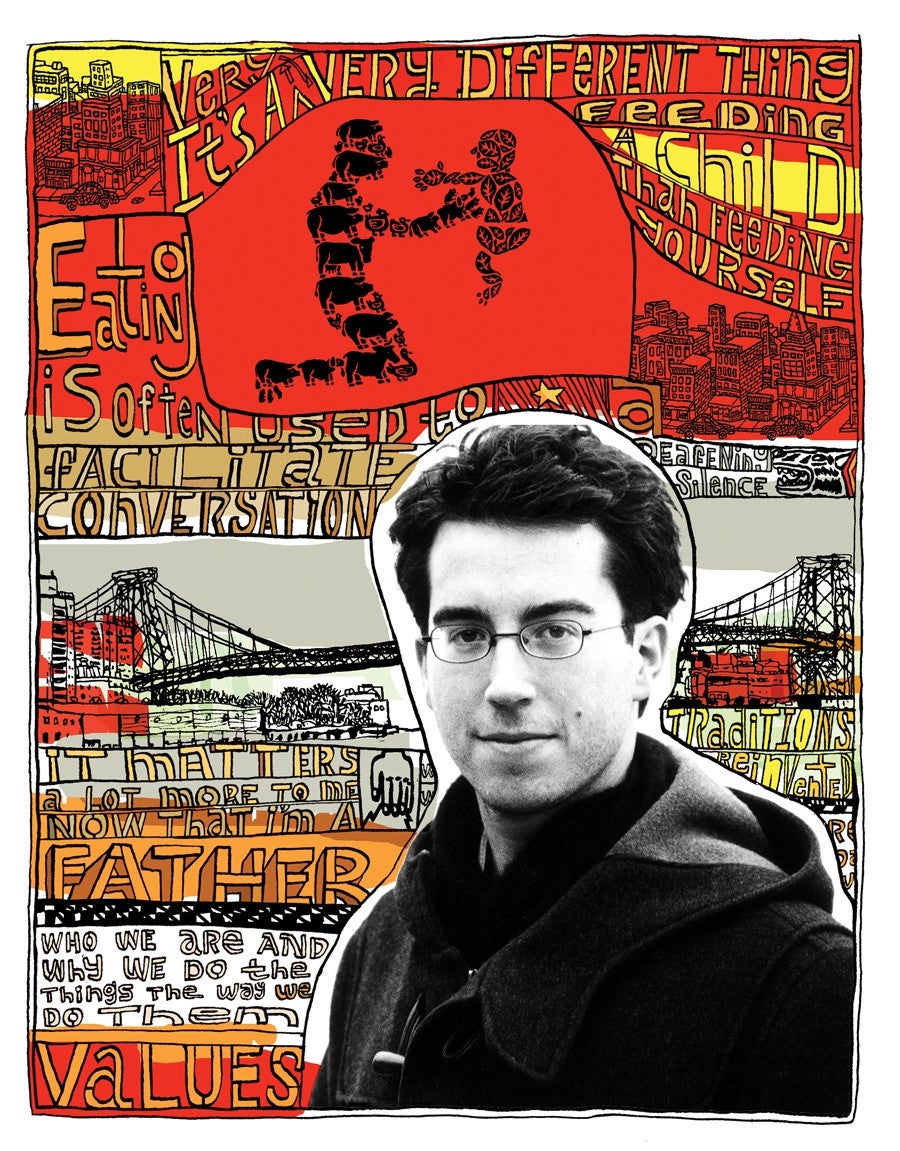

One on One with Jonathan Safran Foer

After publishing two novels, beginning with the widely acclaimed Everything Is Illuminated, Jonathan Safran Foer delves into the subject of factory farming for his first nonfiction book, Eating Animals. An on-again, off-again vegetarian since childhood, Foer began to reconsider his position in 2006, when the birth of his son, Sasha, prompted the question: “What do I feed my child?” VT spoke with Foer, 32, by phone as he walked the streets of Brooklyn, N.Y., where he lives.

Q: How did starting a family cause you to reconsider eating meat?

A: It’s a very, very different thing feeding a child than feeding yourself. I’ll eat a lunch of only French fries, but I don’t want that for my son. I want food to be better than that for him. I want it to taste better and to be a more significant thing. But there’s more to it than that. The environmental effects are so stark: on rural communities, on human health, on animals. It just matters, and it feels, to me, like it matters a lot more now that I’m a father.

Q: People often consider vegetarianism to be solely an “animal rights” issue. How can we shift our language to realize that it’s a human rights issue as well?

A: Why was there such an active effort to refer to swine flu as H1N1? Because we wanted to distance ourselves from that connection. We know where the flu came from: it came from factory farms in North Carolina. The link between flu pandemics and animal agriculture is not an opinion. It’s a well-documented fact by scientific organizations that have no interest whatsoever in promoting vegetarianism. It’s a case of language needing to do a better job.

Q: How are people’s diets affected by the language used to talk about food?

A: One of the fastest-growing sectors in the food industry is cage-free eggs. People want to know that the hens producing the eggs they’re eating had decent lives. The industry takes “cage-free” as literally as they possibly can, which is to say the animal is literally not in a cage. But 30,000 birds in a single roomwhere the space allotted each one isn’t any more than in a cageis simply not what people have in mind when they go out of their way to buy cage-free. Labeling needs to be more accurate.

Q: In Eating Animals, you talk about food, especially meat, in the context of tradition. How can traditions be reinvented so that they don’t further distance us from, as you say, what’s at the end of our fork?

A: Eating is often used to facilitate conversation about what our values are. That’s what’s so great about ritual. The turkey at Thanksgiving isn’t important because it’s a turkey, it’s important because it’s a symbol that makes us think about the past, about how great it is to be American, about what we’re grateful for. But Thanksgiving could be an opportunity to serve a conversation that maybe isn’t served as often as it could beabout who we are and why we do things the way we do. The absence of a turkey is a much better vehicle for that conversation than the presence of one.

Q: Will you continue to write about food ethics?

A: I don’t think I’ll ever write nonfiction again, actually. Factory farming is just a topic I care deeply about, and I don’t think there’s a problem in the world as important that has such a deafening silence around it. I wanted to do my own little part to fill that silence.