Food for Thought: The Quinoa Controversy

For years now, healthy eaters have known a secret. It’s an ancient secret, tracing back to 3000 B.C. in the land of the Incas, where farmers discovered a plant called quinoa and named it their “mother grain.” Like the Incas, vegetarians love and cherish nutrient-rich quinoa, and now, the rest of the world does too.

Quinoa is a tiny, circular seed with a nutty flavor and pearly complexion. It boasts a high protein count and a nutritional breakdown to make health freaks swoon. Once a niche commodity, quinoa has been trending in urban communities over the past few years, gradually developing into one of America’s favorite grains.

Now we can get quinoa in bags at standard grocery stores, over café counters, and on four-star entrée plates. Quinoa shakes have been offered at smoothie and coffee shops. The United Nations even named 2013 The International Year of Quinoa. It’s a big old quinoa party! So what’s the problem?

Refreshing Quinoa Salad

The problem is that quinoa isn’t ours. It’s cultivated by small-scale Bolivian farmers, who have historically regarded it as a dietary staple and source of small profit. But as the global demand for quinoa skyrockets, the strong foundation on which the life-seed is grown is slowly crumbling.

In an effort to cultivate more land for quinoa, farmers are selling or relocating the native llamas who graze there, despite the fact that the llama manure helps maintain the soil. Bad news for the llamas, bad news for the soil.

Further, outside investments in mechanized quinoa farming are pushing Bolivian farmers to prioritize quick, mass production over sustainability. According to the Environmental Advocacy Department of the University of Buffalo, the use of heavy machinery in Bolivia means the loss of 70 metric tons of soil per year. Not to mention that this soil is traditionally given four to six years of rest between sow periods—a practice that has been widely discarded as market prices for quinoa rise. If unchecked, experts say the break-neck pace of production could lead to desertification in a matter of years.

On the bright side, there are alternatives in the works. Since the mid-1980’s, White Mountain Farm in Colorado has been growing quinoa in the Rocky Mountains, where the cool, dry climate and low-nutrient soil help quinoa plants to thrive. But the crop is finicky and can’t be grown in bulk, said one assistant manager, adding that White Mountain is the only quinoa farm in North America. She said it’s difficult to keep up with demand. Of the 71,000 metric tons of quinoa imported in 2010, less than 10,000 pounds were produced in the United States, according to the Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Domestic production is not enough.

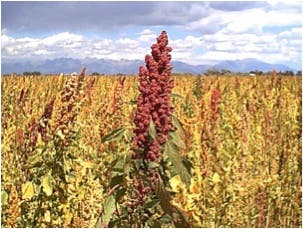

red quinoa image courtesy of White Mountain Farm

There are nearly 3,000 types of quinoa, but the most common strain is Royal Quinoa, available in red, black, or golden, which is probably what you’re accustomed to buying in the grocery store. Studies show that over 95 percent of Bolivian farmers are now producing exclusively Royal Quinoa. This kind of standardization leads to what environmentalists call a monoculture, which can be very harmful for the land.

So what can we do about it? We don’t need to give up quinoa, but we do need to stay informed. On the one hand, the quinoa boom has resulted in huge profit for Bolivian farmers, who can now afford Western commodities previously beyond their reach. The Bolivian government is incorporating quinoa into nutrition packets for pregnant women, and Peru is using it in school breakfasts. So in some ways, the quinoa boom has been a positive force.

But still, the environmental impact of mass consumption is daunting. Domestic production isn’t enough to sustain the demand, but it may be the most plausible solution for those who want to eat quinoa ethically. Also keep an eye out for Fair Trade Quinoa from Alter Eco Foods or La Yapa Organics. Let’s make sure these quinoa farmers (and their llamas) don’t get left in the dirt.

——————

Sammy Caiola is a freelance blogger and reporter who was recently unleashed from the Medill School of Journalism in Chicago. When not writing about the environment, health and wellness, arts, education, LGBT issues, and more, she enjoys hiking and playing the ukulele.