My Curvaceous, Cast-Iron Beauty

Of the many odd, old and quirky things that adorn my kitchen—my husband’s great-grandfather’s hand-forged blacksmith tools, an 1898 apple corer, two muslin embroidery samplers, and my antique Swiss butter and cookie molds—I love none more than the metal contraption that’s clamped to one end of my kitchen counter.

“What is that?” every person who sees it asks. “A sausage maker? Cannoli filler? A corn grinder?” No, no and no.

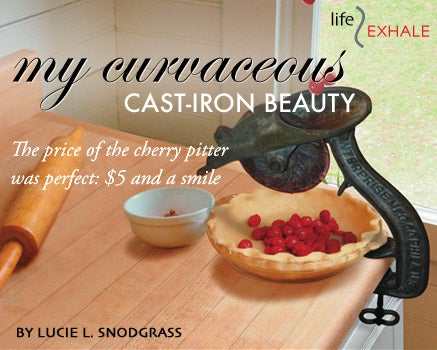

The object of their curiosity is my beloved cherry stoner, a curvaceous cast-iron beauty circa 1890, produced by the Enterprise Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia. Anchored to my countertop, the pitter leans forward from its base like the masthead of a schooner.

As with so many classics, the pitter is simplicity itself. At the end of its silvery neck rests a narrow trough bisected by a disk attached to a metal handle. On the top of the pitter is its model number, 16, and stamped in raised capital letters are the bold words “Needs No Adjusting.” What needs no adjustment is the floating disk that allows all shapes and sizes of cherries to pass through the pitter’s middle. There the stoning work is done. At the bottom, a metal tongue rests against the countertop, and an elegant threaded key with a metal pad forms the moveable part of the clamp. That’s it.

I found the pitter one hot June afternoon years ago, after an impulsive stop at a pick-your-own orchard yielded two sticky hands and 20 pounds of sun-warmed cherries. On the way home, I stopped at a dusty antique shop specializing in carpenter’s tools and inquired, rather desperately, if the owner had a cherry pitter. Actually, the man said, he did—had it forever, couldn’t remember even having acquired it. It was mine for $5 and a smile. Later, as he made change, he asked what I planned to do with it.

When I said I intended to put the pitter to immediate use, he smiled. “I doubt it still works,” he said. “It probably hasn’t been used in 50 years.”

Though I didn’t say so, I knew he was wrong. The pitter weighed as much as a sack of sugar, and it was so lovingly, so lastingly built that I was sure a few decades of neglect had resulted in nothing worse than creaky joints and a thick layer of grime.

Back at the farm, I scrubbed the pitter thoroughly with scalding water and a coarse brush, and as layers of dust and dirt rinsed away, the cherry stoner’s wide mouth flashed a metallic grin, eager to go to work. A thorough drying and a judicious application of vegetable oil, like a fresh coat of lipstick, completed the restoration. The pitter looked, if not new, like a woman in the prime of life.

I attached it to the kitchen counter, tightened the clamp, spun the handle a few times and set it into motion with an encouraging, “Go for it, girl.” I placed two bowls underneath the pitter—one directly under the disk to catch the cherries and another under the trough’s end for the pits. Slowly, I fed a few cherries into the pitter’s mouth and turned the handle. Nothing. I fed it more. Still nothing. Impatiently, I shoved a few more into its mouth.

Seconds later—following a scraping sound as the disk turned, pressed against the cherries and squeezed them—a neat line of yellow pits arrived at the narrow end of the trough, as if poised to jump. In the bigger bowl, the once-fat Montmorency cherries, delivered of their weight, bobbed in a shallow pool of crimson juice. It worked!

I was enchanted. In dizzying succession, I fed the insatiable pitter the entire bucket of cherries, pound after pound, pausing only to empty the bowls and replace them. Fifteen minutes later, it had stoned my morning’s haul with the ease of a waterman shucking oysters. My wrist wasn’t even tired from turning the handle.

I picked more cherries the next day, mostly for the pitter’s sake, and more still the day after, freezing some and cooking multiple batches of cherry preserves.

By week’s end, I knew just how many cherries it took to keep the process flowing uninterrupted and how quickly to turn the handle. I never tired of feeding fruit into the pitter’s wide mouth, or of watching the pits pile up. Just as I had suspected when I first saw the pitter, once it got started, the cherry stoner never wanted to stop.

I keep the pitter out all year, partly because it makes me smile, like finding a wren’s nest in my geraniums. But it’s also there, among other old friends in my kitchen, to remind me to savor simple things—things made by hand that have no motor or fancy attachments but are beautiful and functional nonetheless.

And it encourages me to slow down, to take a break from my computer, to watch the birds as I fix a cup of tea, and to go outside where, if it’s June, the cherries are fat and full and waiting to be picked.

The cherry pies that Lucie Snodgrass makes at her Maryland farm are kept in an old pie safe, on shelves lined with her grandmother’s monogrammed dish towels.